Learning disabilities and what happens when parents die

BBC

BBC“Get a job, fall in love and find a home of my own.”

These were the lifetime ambitions Ellie gave after her mother’s cancer diagnosis prompted a serious chat about her future.

There are fears about what will happen to thousands of adults with severe learning disabilities when their parents die – with 75% believed to have never moved out, according to charity Mencap.

But a group of young disabled friends are looking to “change the system” and build a home of their own to live in with carers.

At her mum’s house, on the the Gower peninsula, Ellie Lane is keen to show off her bedroom.

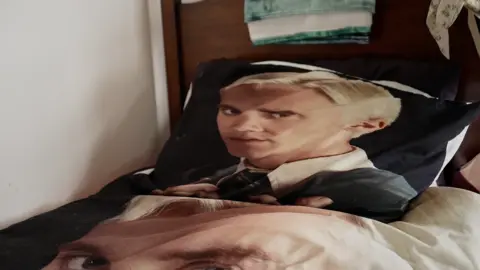

It has a not-so-subtle Harry Potter theme.

The 24-year-old’s favourite character, Draco Malfoy, appears on bedsheets, posters and in life-sized cardboard cut-out form.

She is hoping this collection will soon be following her to a home of her own.

Not so long ago, Ellie’s mum Jane was diagnosed with cancer.

It was the kind of health scare that prompted a serious chat – the theme of which was, what exactly did Ellie want from her life?

The answer was simple, as Jane explained: “She had three ambitions. First of all, was to fall in love.

“Second, was to get a job that was paid.

“And the third one was to leave home.”

Ellie’s neatly laid-out work uniform and grinning pictures with her boyfriend show she’s been successful with the first two.

The final one though, as for so many people, has proved much harder.

Ellie has Down’s syndrome and Type 1 diabetes, so will need support wherever she goes.

While adults with learning disabilities can apply to their local authority for housing, options are limited, according to Jane, a recently-retired nurse.

Ellie would get little say in where she went or who she lived with.

Charity Mencap said around three quarters of adults with a severe learning disability still lived at their family home, with parents often telling staff they hoped to outlive their children, for fear of where they might end up.

With the cancer diagnosis giving Jane a new “focus”, she found a group of similar families nearby – many old school friends of Ellie’s – who were looking to start something called a housing cooperative.

It is a type of housing that has existed since the 1800s, and more commonly sees houses shared between groups of like-minded people – like those hoping to live off-grid.

Each resident has an equal share of the house – and gets a say on how it is maintained and who else lives there.

After almost seven years, the group believe they are just a few months away from legally becoming a housing cooperative – which will allow them access to housing grants to build their home, without the families having to put any money in themselves.

The group, made up of eight families, want the model to offer their children a surrogate family – along with a secure place to live out their remaining years, long after their parents are gone.

For Ellie and her friends, their hopes are more immediate.

They are looking for somewhere close to Swansea city centre, ideal for nights out with friends.

Andre Van Wyk, Cwmpas

Andre Van Wyk, CwmpasThey would like to have their own bedroom and bathroom, but share a kitchen and living room, with space for live-in carers.

“I just want my own space and to have the best time of my life,” said Ellie.

“We could have a girls’ night in – or a girls’ night out.

“I just want to be more independent.”

Planning to live with Ellie is Elin, 26, from Swansea.

Her mum Alison also accelerated the search for a long-term home for her daughter after becoming seriously unwell.

“One of the things Elin has often said to me is ‘who is going to look after me when you’re gone?’,” explained the 59-year-old.

“She loves Lego and she loves Disney. She enjoys her life, but we’re 30 years older than her. It’s not ideal for a 26-year-old woman to be spending all their social time with their parents.”

The hope is they will be in their new home by 2026.

The group currently meets once a month to practice cooking, as well as chatting about décor.

Alison said the parents had considered trying to fund the project themselves, but realised they risked still being tied into their children’s lives long after they had the capacity to help them.

“We want this to be a new way of doing things, one which will change the system,” said Alison.

‘I hope they die before I do’

In Wales, there are around 16,000 adults with a severe learning disability, but only 4,000 of them are living in supported accommodation.

It is thought the remaining 12,000 – 75% of the total – still live at home.

“What you always get blown away by is when families say to you ‘I hope they die before I do’,” explained Wayne Crocker from Mencap.

“That’s an awful place to be as a parent.”

Mr Crocker said the housing situation for those with a severe learning disability was “complex”.

But ultimately, almost 20 years since the last institution closed in Wales, there was still too little housing stock – and too much expectation on families.

“Lots of people live with their parents until sadly they pass,” he said.

“For many it means there’s the shock and the sadness of losing their mum or dad, and then suddenly they’re having to find emergency accommodation too.”

The Welsh government said it is “committed to improving accessibility in social housing” and has invested in building new homes for this purpose.

It added it provided grants to local authorities and housing associations to make homes suitable.